In the next newsletter, we'll review the state of environmental building certification. For now, let's explain the basics of the most advanced one available: the Living Building Challenge of the International Living Future Institute.

The LBC is based on seven categories - called Petals - of design orientation:

- Place

- Water

- Energy

- Health + Happiness

- Materials

- Equity

- Beauty

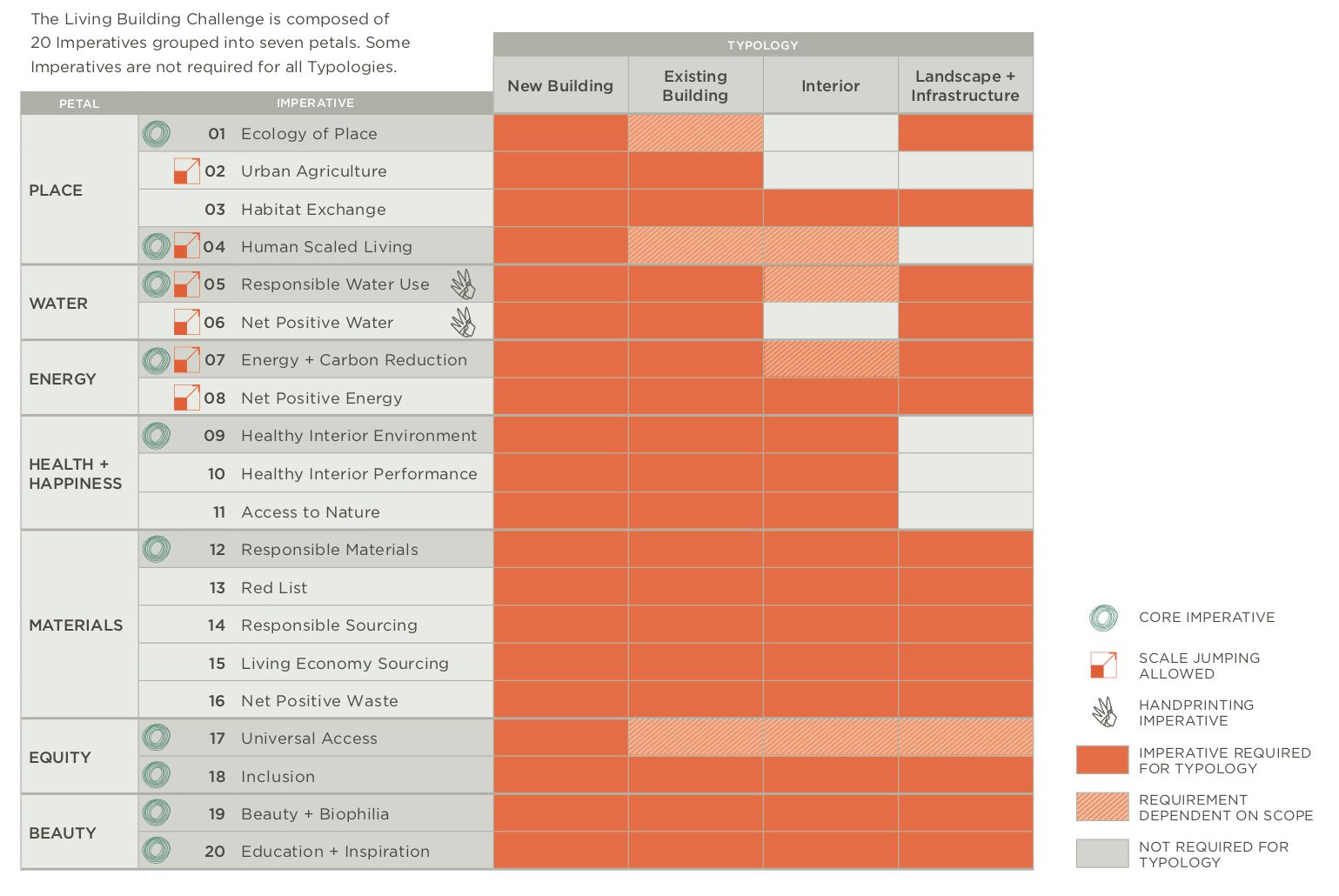

These Petals are further divided into Imperatives group together the specific actions that will shape the sustainability of a building designed with the support of the framework.

This categorization is comparable to the thematic organization of priorities under the main competing standards, LEED from the US and BREEAM from the UK.

But first difference between the LBC and the other certification standards is that the Petals have essential features that must be included for any certification to be possible. Ten of the Imperatives are Core Imperatives, required for any version of an LBC certification.

This is different from LEED and BREEAM which are points-based systems: real estate developers can cherry-pick categories that are easier or more affordable for them, with regard to the overall requirement of sustainability.

If you want to make a real difference, not just brand your building, this matters: sustainability is about real issues to deal with, and points-hacking is not getting down to them.

Another major difference, quite new in the LBC, is the concept of location category, called Transects in the Framework.

Like other standards, versions of the LBC apply to any building at any stage in its life. But the Transect concept distinguishes the follow types of location:

- Natural Habitat Preserve

- Rural Zone

- Village or Campus Zone

- General Urban Zone

- Urban Center Zone

- Urban Core Zone

These zones add or reduce pressure related to the specific context of the development. For example, developments are heavily restricted in the Natural Habitat Preserve: this prevents the absurdity, possible under other standards, to destroy nature to build a new building, and then 'include nature' in some landscaping concept.

One of the most powerful aspects of the LBC is the provision for scale-jumping: meaning that Imperatives for any one building can be considered at a larger scale, rather than just at the individual building's level. This is crucial, and has been a flaw of green building certifications since their start.

It applies mainly to energy and water, and is basically an invitation to think in efficient and infrastructural terms.

It is exciting to imagine that a self-sustaining house with a solar panel in the roof is the pinnacle of sustainability. But it's likely that rooftop solar at small scale is materially and energetically inefficient compared to large-scale provision, such as district heating.

The most convincing differentiator of LBC versus other certification schemes is its focus on operational performance. One of the areas where LEED falls down worst is in the overall energy performance of a building in use, rather than as projected when designed. To get an LBC certification, you must measure performance of the building for a year.

LBC is still at a small scale compared to LEED and BREEAM, but it's by far the most credible statement of intent for any building or developer that wants to achieve sustainability.

For developers and building owners that use the LBC, the certifications available are these:

- Zero Carbon/Energy: Specialist certifications for buildings focussed only on energy and carbon emissions.

- Core: For buildings that achieve sufficient sustainability in all ten Core Imperatives.

- Petal: For buildings that achieve the Core certification, and all the other Imperatives in a specific Petal.

- Living Building: For buildings that achieve results in all 20 Imperatives.

Some developers are developing their own methods and frameworks, which is also exciting, but these can be distorted by other priorities. LBC has a mission that is very clear and focussed.

As a taste of the commitment of the LBC consider the introductions to their Place and Beauty Petals: these go far beyond any box-checking approach to green building, into the deeper reason for sustainability in the first place:

The Place Petal clearly articulates where it is acceptable for people to build, how to protect and restore a place once it has been developed, and how to encourage the creation of communities that are once again based on the pedestrian rather than the automobile. In turn, these communities need to be supported by a web of local and regional agriculture that encourages the consumption of local, fresh and seasonal food.

The intent of the Beauty Petal is to recognize the need for beauty and the connection to nature as a precursor to caring enough to preserve, conserve, and serve the greater good. As a society, we are often surrounded by ugly and inhumane physical environments. The key to creating beautiful buildings is to embrace a biophilic design process that emphasizes that people and nature are connected and the connection to place, climate, culture and community is crucial to creating a beautiful building.