Economics is the dirty sweaty gladiatorial arena at the centre of all sustainability debates. No matter how ethical, creative, political, practical, visionary you want to be about environmental issues, you will end up being sucked into the vortex of issues, ideas and critiques about how the economy generates, or reduces, resource consumption and nature damage.

The main event in this terrain is the fight over economic growth. There are broader debates over the foundational science and political justice of, and implications of the info age for, economics and growth - but let's get basic clarity on sustainability and growth.

We don't need to know necessarily, as environmentalists, very much about economic growth as environmentalists if we know one thing: is environmental impact, that is consumption of resources and damage to nature, increasing or decreasing as a result of economic growth. Economic growth could be going up or down, but environmentalists want to track environmental impact.

This invites us to differentiate different types of economic growth, which is already a help. Whenever there is a pitched fight about economic growth, both sides can be partly silenced by being compelled to observe, respectively, that some growth has less impact and other growth has more impact. Debates should start there.

The very smartest debaters on economic growth have indeed started there ... and still come out on different sides of the argument.

Vaclav Smil, the natural science super-researcher, supported by Bill Gates, says that economic growth cannot continue. David King, the former Chief Scientist in the UK, says economics is very wrong and has caused huge damage.

Amory Lovins, the original pioneer of ecoefficiency, continues to believe that economic growth can reduce impacts. And Andrew McAfee, the newest and most compelling super-exponent of newwave ecotech is convinced and convincing that economic growth leads the efficiency revolution.

What is missing here, part of the root problem with economics and thus growth, is a foundational theory of differentiated growth. None of these very smart folks can really say for sure this kind of economic growth is bad, and that kind of economic growth is good. The debate thus devolves to a dance-off of of statistics: look at the rising impact in this industry! looking at the increasing efficiency in those products!

Technically, the main theory that is needed is a systematic theory of absolute decoupling. I'll explain.

One of the best differentiators of economic growth in terms of environmental impact is decoupling. This means is the amount of some environmentally important variable is coming down as economic growth goes up.

Relative decoupling is what happens when the rate of growth of impact starts becoming lower than the rate of economic growth. This would mean that that some kind of economic activity is gradually becoming more efficient over time. Not a bad thing! But impact could still be growing.

Absolute decoupling is something very different. This is a situation where impact stays the same or reduces as as economic growth continues. Ideally, the impact will go down continually, as the economic value goes up. And you can find some of it, which is definitely a good thing!

But even where you find absolute decoupling, let's say in a specific sector like computation - the economic value provided by chips has exploded while the energy and resources required have collapsed - it's very hard to understand how to apply whatever magic caused such a break between impact and value to any other sector, let alone to a whole economy.

It's hard not just because there's no theory of absolute decoupling, but no systematic theory of absolute decoupling. A successful systematic theory of decoupling would be one where impacts always go down not just sometimes, and we really truly need this.

Without it, it's just instructive but anecdotal evidence. If a treatment reduces the symptoms (of unsustainable economic growth), but isn't understood and can't be used in all cases, you can't call it a cure.

So, for all the proponents of growth-as-answer to sustainability, even those with evidence of absolute decoupling, the correct response is: do we have a systematic theory, or are you hoping for the best here?

At the same time, it's not reasonable for critics of green growth to claim that absolute decoupling just has never been found, or that there are obvious trends of industrial decoupling overall, and that there's thus no evidence for any of this.

The branch of conventional economics that should have come up with a real theory of decoupling by now has totally failed to do so: so-called environmental economics has got stuck with very limited theory around pricing of 'external costs', which leads to bizarre pseudoscience like asking people how much they would pay for a stable climate, or to save ocean turtles (10 dollars? a billion dollars I don't have? a trillion dollars taxpayers don't have?).

But neither have the three pioneering new fields of economics that are supposedly built on environmental science grounds:

- ecological econonomics

- industrial ecology

- systems ecology and resilience science

None of these have served up systematic theories of decoupling. So for now, if you go looking, the closest you will get to understanding the theory of systematic decoupling in specific sectors - or its impossibility - is lots in the weeds of physical and mathematical modelling of economic input-output, resource flow models, economic systems.

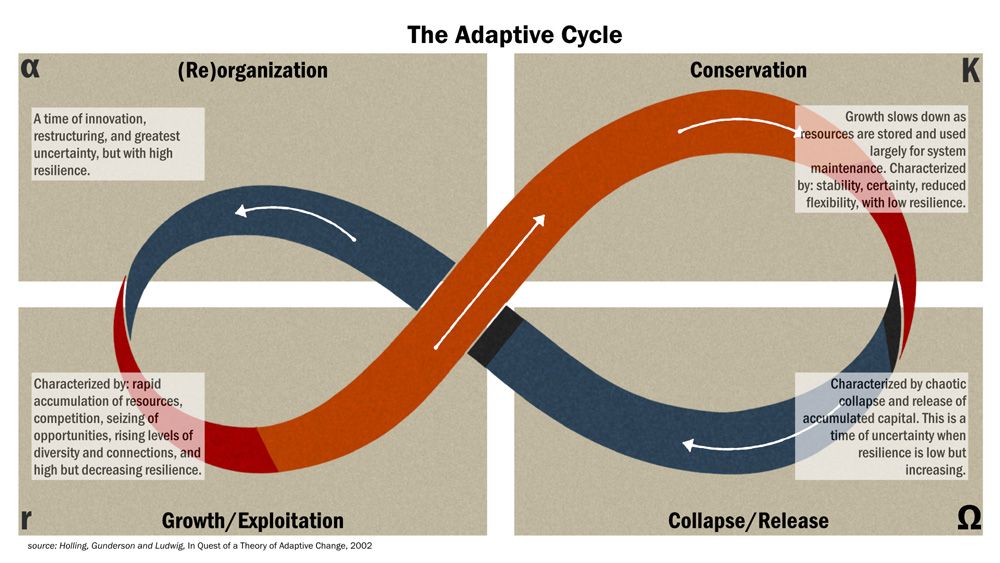

If there's a single, promising idea to come out of alternative economics relating to differentiated growth, and absolute decoupling, it's the so-called adaptive cycle which has been taken from systems ecology.

It's a framework for how, as ecosystems form, they rapidly accumulate biomass, as communities of plants and animals grow, but over time, the ecosystem reaches a climax state and total biomass of the ecosystem is just maintained at a stable level of time. But climate ecosystems aren't static: they continue to grow, in numbers and refinement of species, and thus overall complexity, over time. Some plants event continue to grow: trees add leaves and rings, even if they don't continue to grow upwards to heaven.

This pattern, of stabilizing physical mass while growing in sophistication and features, looks a lot like something we might expect from a systematic theory of decoupling: more from less. But we no-one has yet extracted that theory from the adaptive cycle of ecology: we just have some indications of decoupling, and criticisms of their universality.

Is there anything practical to takeaway from the differentiated growth, and in particular decoupling, issue? Can we apply or just consider how it might be applied to daily life for modern citizens and consumers?

One idea that has taken off in practice without the theory driving it or even helping it, is the shift in modern urban living to an asset-light lifestyle, or the commercial sharing economy. This idea is really only an overlapping group of principles, and only fragments of it are present in any one practice, but the general idea is, rather than every individual owning their own basket of material goods, and then not using them very much, people 'share' a collective pool of physical assets, enabled by commercial 'sharing' systems. This leads to, in principle, less resource use per person, and hey presto! decoupling!

Not just because the evidence for the decoupling effect of the commercial sharing economy is limited, but also because some people just don't believe in growth or decoupling at all, there is a healthy degrowth movement, overlapping with the an economic 'steady state' - ie no-growth - strategy.

Folk who push these ideas have a very clear strategy for environmental sustainability. Less stuff. Produce less, buy less, use less, dispose of less. Rediscover the boundary of needs vs wants, and reduce the attention to unnecessary wants. How this is supposed to work theoretically is about as unclear as systematic absolute decoupling is, as a theory. There's certainly no accepted systematic degrowth theory, showing how any economy could just reduce growth from its current state, while not reducing quality of life, or experiencing major shocks.

But that doesn't stop people from believing in it passionately!Just as there's plenty of evidence of real decoupling, there's a lot of evidence of at least individuals if not whole societies 'downshifting', living the degrowth life, pretty happily.

If you investigate degrowth, however, and line up its strategies for living with less, and shrinking the economy accordingly, you discover something pretty interesting. It's that if there is a theory of living well with less in a degrowth regime, it's about as close and allied to the adaptive cycle efficiency of an ecosystem efficiency over time as ... industrial decoupling and commercial sharing economy is.

This should all be pretty embarrassing green growth and degrowth theorists: both that none of them have any confirmed systematic theories, but also that their main big ideas, more from less, are basically shared.

What's particularly striking is that the the commercial sharing economy of Uber and AirBnB, is functionally indistinguisable from the sharing economy of degrowth, sometimes called the peer-to-peer sharing economy. Even if you claim that centralized sharing leads to a mistaken motive - profit instead of efficiency - it's not actually clear that decentralized sharing models are actually any more efficient.

What happens over time is that the fight over green growth tends to generate more similarities than differences in actual proposals, even if it also reveals fundamental differences in institutional goals, distribution of economic rewards, personal motivations, and organizational starting points.

If degrowth people say they don't like the cult of efficiency that drives green growth narratives, you can openly ask them what they think becoming a better farmer or baker means, other than having a larger harvest or better bread for the same inputs of effort and resources. If they answer, they just don't like growth!, you could wonder aloud if that means they don't want society to have more books, plays, poems, songs, symphonies, nature experiences, friendships?

And if growth folks say they doubt that downshifting and stepping off the material economy is possible, ask what they think the theoretical underpinning of Uber, WeWork, AirBnb, even digital movie rental, actually is. It's not any kind of production efficiency, even if that - given absolute decoupling - really could help to create a sustainable society. The rise of asset-light, commercial goods sharing is some other kind of decoupling that really can't be explained in the same way as industrial decoupling of resource extraction and manufacture.